Del Monte's Downfall: A Cautionary Tale for Legacy Brands

BUSINESS & INNOVATION

The company "didn't fail because people stopped eating canned food—it failed because it stopped evolving while the market moved on."

For some Indonesians, the name Del Monte might not be a household name in the same way as local brands. Yet, a trip down the canned goods aisle of any major supermarket, and you'll spot it: the iconic shield logo on a bright yellow can, a reliable fixture on the shelf. This brand, Del Monte, is a giant of the food industry, with a history spanning over a century. Its story began in the late 1800s with a group of canneries in California, eventually consolidating to become Del Monte Foods in 1916. While the Indonesian entity operates as a separate business under a multinational based in Singapore and the Philippines, the US company's recent news is a major headline for the global food industry. After an astonishing 139 years in business, Del Monte Foods, the American entity responsible for those signature cans, has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

Del Monte's bankruptcy is largely presented in the sources as a cautionary tale about brand inertia and failure to modernize in a dynamic food economy. The company "didn't fail because people stopped eating canned food—it failed because it stopped evolving while the market moved on." This highlights a fundamental inability of the legacy brand to stay in sync with contemporary market dynamics.

Failure to Adapt to Shifting Consumer Preferences

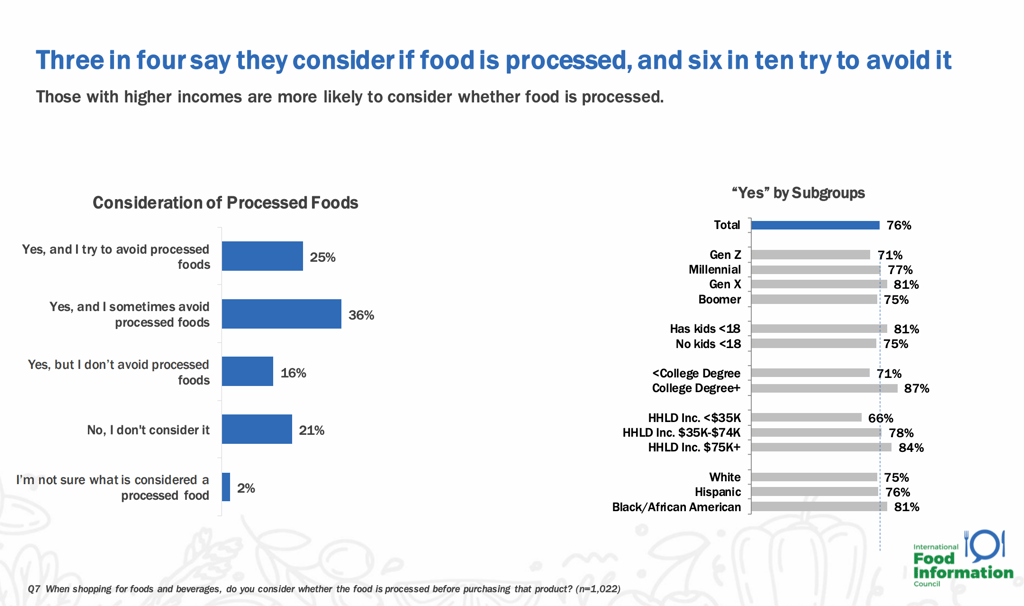

Del Monte's decline is the story of a company that was never able to keep up with its consumers. For decades, Del Monte's name on the label of canned vegetables and fruits was equated with the height of modern-day food preservation. In addition, a recent study by the International Food Information Council (IFIC) highlights that three out of four consumers consider whether a food is processed, and six in ten actively try to avoid it. This is particularly true for higher-income households and those with higher levels of education.

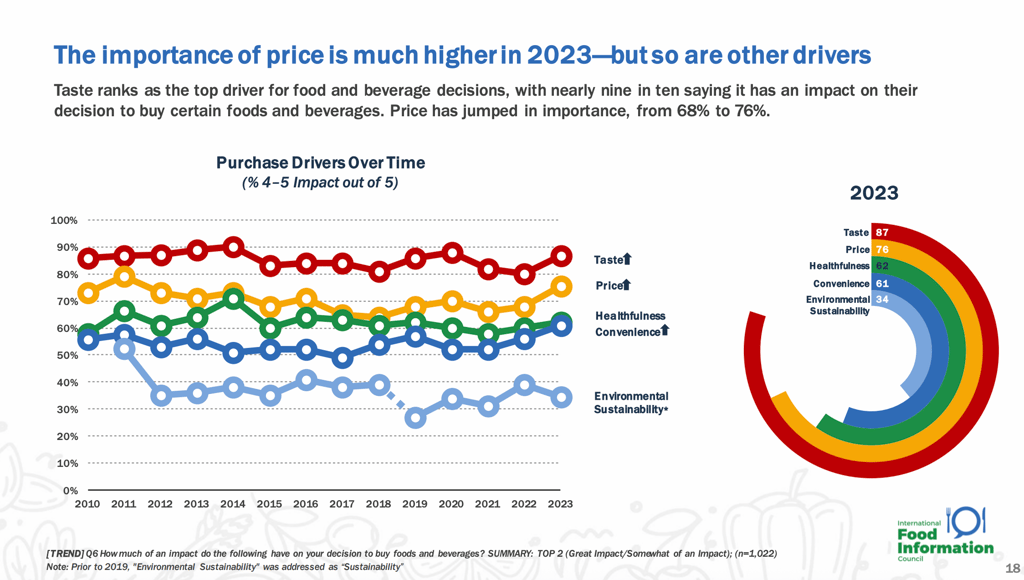

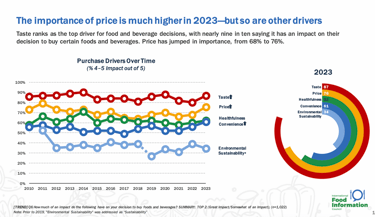

Furthermore, while taste remains the top purchase driver, its importance is closely followed by price and healthfulness, both of which have been on an upward trend. Ultimately, Del Monte's reliance on its staple product line has left the company unaligned with a marketplace that has shifted to demand healthier, less-processed alternatives, as revealed by these underlying shifts in consumer values.

Lack of Product Line Evolution and Branding Adaptation

A major reason for its disappearance is the inertia shown by Del Monte's brand. The company did not make appropriate arrangements concerning their product lines and brands suitable to today's taste, and its "signature yellow-labelled cans" were no longer relevant. Critics have pointed out that the company remained stagnant, offering no evidence of introducing healthy versions of its core products or exploring alternatives beyond canned food. Such a lack of innovation was a profound misstep during an era when health consciousness was growing.

Rise of Private Labels and Price Sensitivity

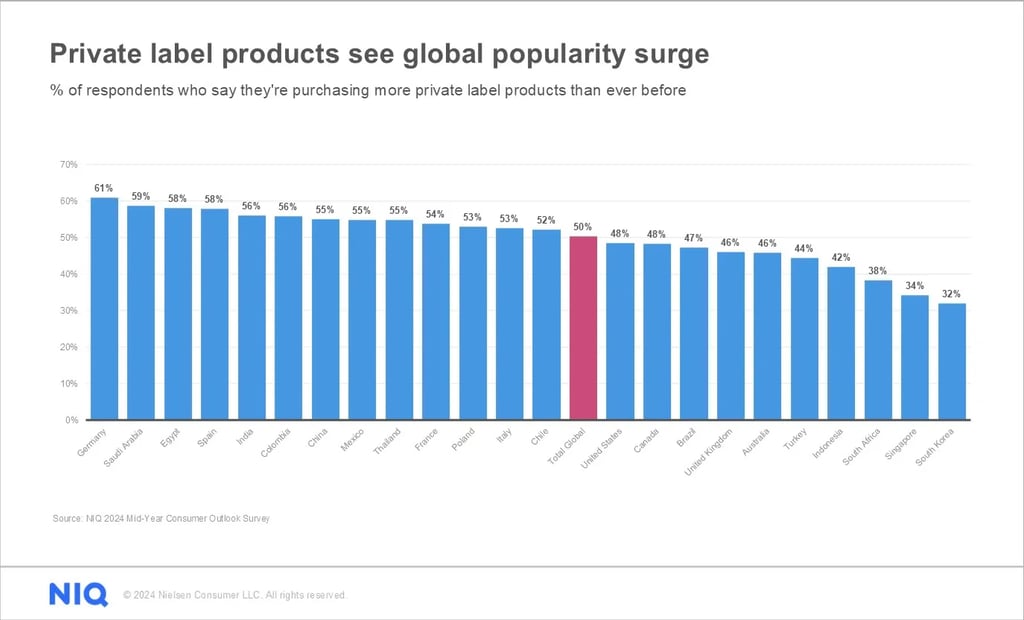

Del Monte's misfortunes were aggravated by its inability to fight in a "centre-of-store battlefield now dominated by agile private labels." In the face of relentless inflation, price-conscious consumers increasingly turned to lower-cost store-brand canned vegetables rather than to traditional brands. This is not merely a local phenomenon; it's a global trend. Although Europe has led private label adoption for decades, a new survey found that in markets from Saudi Arabia to India, shoppers are buying more store brands than ever, with 50% of worldwide shoppers going beyond the previous pace.

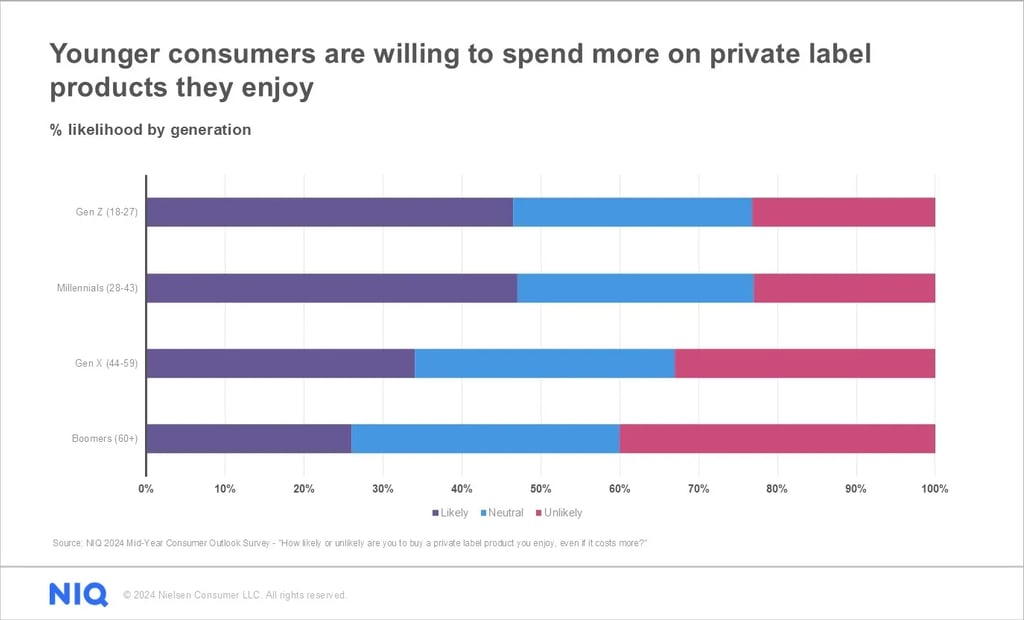

This trend is particularly prevalent with younger generations. The Mid-Year Consumer Outlook survey revealed that two times more Millennials and Gen Z (46%) would pay more for private label brands than just 23% of Boomers. These emerging generations, who are quickly developing their purchasing power and brand loyalties, see private labels as not just a cheaper alternative but as a legitimate and often innovative one. Though private label players have since enrolled to cover an estimated 40 to 45 percent of the total market, Del Monte's central failure lay in its failure to position its canned goods separately from these competitors, thus losing a gigantic chunk of market share since customers saw no good reason to pay a premium for something which they no longer perceived as superior.